We are delighted to share this post by Katie Learmont. Katie, our Graduate Business Partner Technical Assistant, has been working at the Digital Humanities Lab for four months as a Technical Assistant. Prior to joining the team, she undertook a masters in Library and Information Studies at UCL and has worked and volunteered in a variety of settings, including Eton College, the Royal Academy of Arts, V&A and the European Parliament. Katie’s experience sparked an interest in how 2D and 3D digitisation can benefit academic teaching and research, and led her to join the Exeter Digital Humanities team.

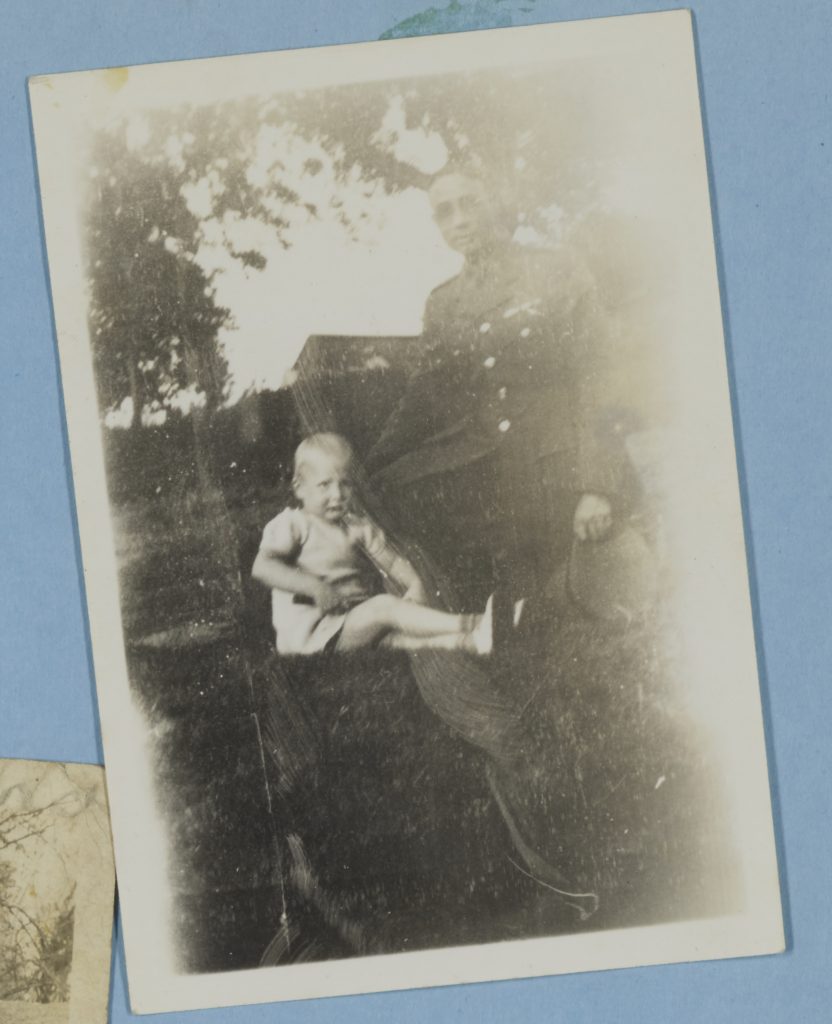

One of my key responsibilities as Graduate Business Partner was to support our Intern team to undertake a small digitisation project relating to Muslim Indian soldiers in Europe during the Second World War. On 3rd December 1939, 1723 men, mainly “Punjabi Mussulmans” and 2000 animals left Punjab for France to assist the British army with transporting supplies and equipment over rough ground. After they were evacuated from Dunkirk in May 1940, many RIASC (Royal Indian Army Service Corps) soldiers settled in military camps across the UK before returning to India in February 1944. Four RIASC men were billeted with Herbert Foster, who ran a tree nursery and chicken farm at the Plateau, Shirley Hollow. In 2016 Foster’s daughter, Betty Cresswell, met with Ghee Bowman (who is currently undertaking an AHRC funded PhD research project) at her farmhouse in rural Derbyshire. Betty showed him a small photography collection, featuring her parents with Captain Gian Kapur (Gian Kapur corresponded with the family regularly until his death in 1985), and the others, as well as press cuttings, letters, slippers and brass objects. Betty had met the Force K6 soldiers in 1940 when she was just three years old, and although she couldn’t remember them clearly she could remember the smell of chappaties cooking!

Work on digitising Betty’s collection began in May, when Ghee visited the Digital Humanities Lab to discuss his ideas. He explained to us that he had taken photographs of Ms Cresswell’s collection, but was disappointed with the quality of the images. He wanted to acquire professional quality scans of the papers and other objects to aid his research, as well as preserve the memory of Force K6. Despite the significant roles the soldiers played in the war effort, they have seemingly been ‘whitewashed’ from history. Indeed, the Ministry of Defence initially claimed there were no Indian troops at Dunkirk and more recently the blockbuster “Dunkirk” was criticised for not portraying any Indians. Ghee gave a presentation to our undergraduate interns, which explored these issues in greater depth, and we showed him our digitisation facilities in Lab 1.

The images were captured using Phase One “Capture One” software. This programme offers many benefits to users, for example the interface could be customised according to customer needs, accurate colours could be obtained and different file formats could be imported and exported speedily. We also used a Schneider Kreuznach 240mm lens and an iCAM archive system copy stand. The latter allowed us to flatten documents without spending time carefully rearranging them or adding extra support like snakes and book weights (this would have potentially obscured important information in documents and photographs). To ensure a smooth completion of the project (Ghee wanted the project to ideally be completed by the end of June) we devoted a few hours a week in Lab 1 to digitise the collection alongside other activities.

Many photographs were glued to separate leaves of standard A4 paper. In order to digitise individual images, the pages were digitised in the entirety and cropped during the ‘processing’ stage. The overhead lights present in Lab 1 also on occasion resulted in light reflecting off the copy stand’s glass plate and we were careful to adjust lighting were required.

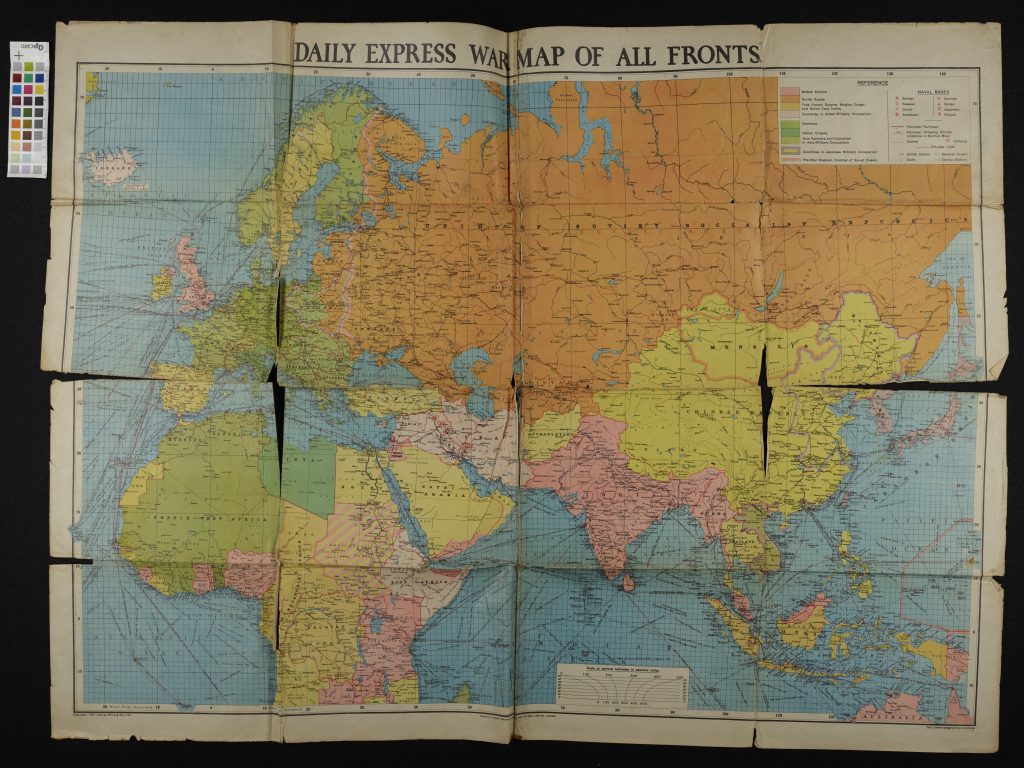

Another issue we encountered was digitising the Daily Express “War Map of All Fronts” present in the collection due to its vast size and small text. The fragile condition of this document also meant we were unable to place it underneath the glass plate in case the paper would deteriorate even further. To overcome this, we photographed the map from a significant height using a 50mm lens. We decided not to photograph “chunks” of the map and stitch the images together, as this would have been time consuming and a more robust copy could be purchased easily and cheaply online.

Post processing work involves cropping the images, undertaking any photo editing (if necessary) and converting the files into JPEGs and TIFFs. The uncompressed TIFF format means no image data is lost after scanning. This is ideal for archival images when all detail must be preserved and file size is not a consideration.

Happily, Ghee said that he was “overjoyed” by the resulting scans, and that they could enhance his research, be used in future publications and his thesis. He also stated that Betty would be able to show the images to friends and family members and the memory of this extraordinary period of history and friendships could last for decades.

Our undergraduate Interns team and staff very much enjoyed participating in this project!