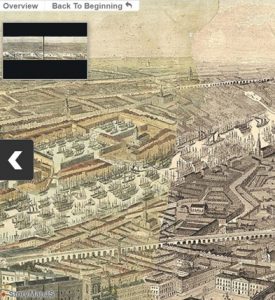

We are delighted to present an interactive map of the print of Smyth’s Panorama of London held in The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum’s collection (see here: EXEBD 12796):

https://humanities-research.exeter.ac.uk/bdcm/panorama/bdcm_bl_complete_storymap.html

In the blog-post below, Ollie Anthony, Technical Assistant at the Digital Humanities Lab and former BDCM museum volunteer, explains the significance of the panorama and the digitisation process involved in creating the interactive map.

The initial Panorama of London produced in 1845 by James Frederick Smyth and printed by William Little of 198 Strand, London, was commissioned by the Illustrated London News, the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine. This blogpost discusses the history of the London panorama, as well as the processes used to digitise a colourised copy, held as part of the Bill Douglas and Peter Jewell Collection at The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum (BDCM).

Despite its name, much of the contents of the popular Illustrated London News magazine series pertained to events happening around the world, particularly the far-reaching parts of the British Empire. Their magazines, often jeering and comical in style, were well known for their eclectic and extravagant displays of London life, politics, and royalty. On January 11th, 1845, upon the beginning of its third year of publication, readers were able to pay One Penny to purchase a copy of the Panorama of London or receive a free copy if they subscribed to the weekly Illustrated London News.

Smyth and the panorama

James Frederick Smyth was originally commissioned by the Illustrated London News to produce the Panorama of London as a 12-page supplement. Besides this, a nine-page ‘History of London’ was printed, as well as a Key to the Panorama which provided place names for each significant scene or building in the panorama. Later full-size copies of the panorama, as shown on the BDCM’s website, had a total length ‘upwards of eight feet’.

Figure 1: An advertisement by Illustrated London News for their publication of the Panorama of London.

Given the extent of the project, it is likely that Smyth illustrated the panorama in 1844, in the year and months leading up to its publication in 1845. The advertisement shown in Figure 1 points to the fact that the illustration ‘occupied the Artists for several months, so that the strictest reliance may be place on its accuracy’.

As with many Victorian print makers, Smyth’s legacy is today primarily observed in his surviving published prints. While little can be said about his personal life, his works reflect his long-lasting career as a print maker and wood engraver. Besides the Panorama of London, Smyth also produced numerous other prints over a period of twenty-five years from 1842-1867, for publishers including Charles Knight’s magazines (Charles Knight & Company), William Little, and the Illustrated London News. Some of these prints fit more closely with the style and conventions of the Illustrated London News, including portraits and scenes containing multiple people and often politically focused. The creation of the panorama is described by ILN as having ‘the highest talent employed in its execution’, suggesting that Smyth held a reputation as a very capable artist, thus explaining why he was commissioned to illustrate the panorama in the first instance. With the Pictorial Times, ILN’s biggest rival, publishing the Grand Panorama of London from the Thames shortly after Smyth’s own engraving, it is clear that such depictions were very much in vogue at the time, with London magazine publishers competing for similar conservative audiences.

Figure 2: The seven oldest children of Queen Victoria, by Frederick James Smyth, published by Illustrated London News, after Unknown artist. Published 25 December 1852. Borrowed from the National Portrait Gallery under a CC (4.0) License.

Occasionally, Smyth’s prints were produced ‘after’ an artist, meaning that the illustration was not of Smyth’s initial creation, but instead in the style of another illustrator or a direct imitation – as with Figure 2, which is by Smyth, ‘after Unknown artist’. This indicates that the illustration was conceived by another artist, while it was Smyth who was responsible for carving it into wooden blocks ready for pressing in the printing process. In the case of the Panorama of London, six wooden blocks were carved and then held together to form the panorama in its entirety. Looking closely at certain parts of the panorama, vertical lines demarcate the points at which each wooden block ends.

London in the panorama

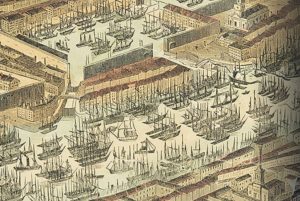

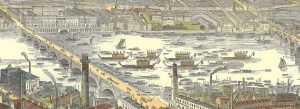

The specific brief given to Smyth in order to create the panorama remains a mystery, although it is possible to hazard a guess from a detailed view of his final piece. Given its heavy focus on the River Thames, a mysterious ceremonial parade, and the multiple bridges crossing it, Smyth’s intention was clearly to highlight the topographical importance of the Thames to London, as well as its integrity to social, political, and royal life.  Moreover, his focus on particular buildings, primarily those of traditional national value, such as the Palace of Westminster, the Royal Exchange, the Tower of London, and so on, suggest that his mission was to show London in all its splendour and richness, no doubt to appeal to the strictly Conservative readers of the Illustrated London News at the time. Besides this, the streets are lined with the spires of chimneys and statues, elucidating the centrality of religion and imperial gain to the lives of many Londoners at the time.

Moreover, his focus on particular buildings, primarily those of traditional national value, such as the Palace of Westminster, the Royal Exchange, the Tower of London, and so on, suggest that his mission was to show London in all its splendour and richness, no doubt to appeal to the strictly Conservative readers of the Illustrated London News at the time. Besides this, the streets are lined with the spires of chimneys and statues, elucidating the centrality of religion and imperial gain to the lives of many Londoners at the time.

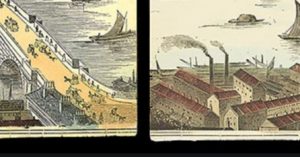

The bustling River Thames is also crammed with commercial boats, hay and coal barges, paddle-steamers, dredgers, with a mass of shipping below London bridge, and HMS Dreadnought and the Grand Surrey Canal seen to the east. Smyth leaves little doubt that this really is the trading centre of the world.

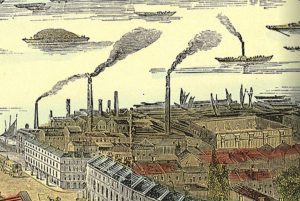

Added to this are the huge industrial upheavals, depicted here with towers of billowing smoke venting from chimneys and factories lining the South Bank. It is easy to forget that these could be held at least partially responsible for the numerous clouts of smog and stinks which have come to be associated with the period, as immortalised in satirical cartoons such as those published by the ‘Punch’ magazine, including the ‘Silent Highwayman’ shown in Figure 5.

Since Smyth glosses over many of the more noxious elements of nineteenth century London, the panorama was clearly a celebration not only of the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine, but also of the perception that London was the greatest industrial city in the world. The aerial perspective drawn out by Smyth afforded Londoners the opportunity to dazzle at the size and complexity of their city, while tarnishing out the harsher realities facing public services and poorer communities. Laden in bright yellows and golds, the rarer colourised copies such as the one held in The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum supplant supposedly cynical realities of poverty with filtered notions of liveliness and beauty. And, as viewers find themselves situated high and above the city of London, so too is the City framed eminently central to the industrialised world.

Digitising the panorama

The Panorama of London digitised in this project is an original item attributed to the founding collection of The Bill Douglas Cinema museum.

Figure 6: Panorama scrolls, laid side-by-side, showing detailed discontinuous elements.

Comprising of two scrolls, the panorama completes a view of London from Westminster to Greenwich. The two parts are likely to have been produced separately since while they depict one continuous scene, there is some discontinuity in close-up details between the two (see Figure 6). Besides the two-part panorama, an accompanying key is also kept by the museum, this can be seen on the second slide of the interactive map.

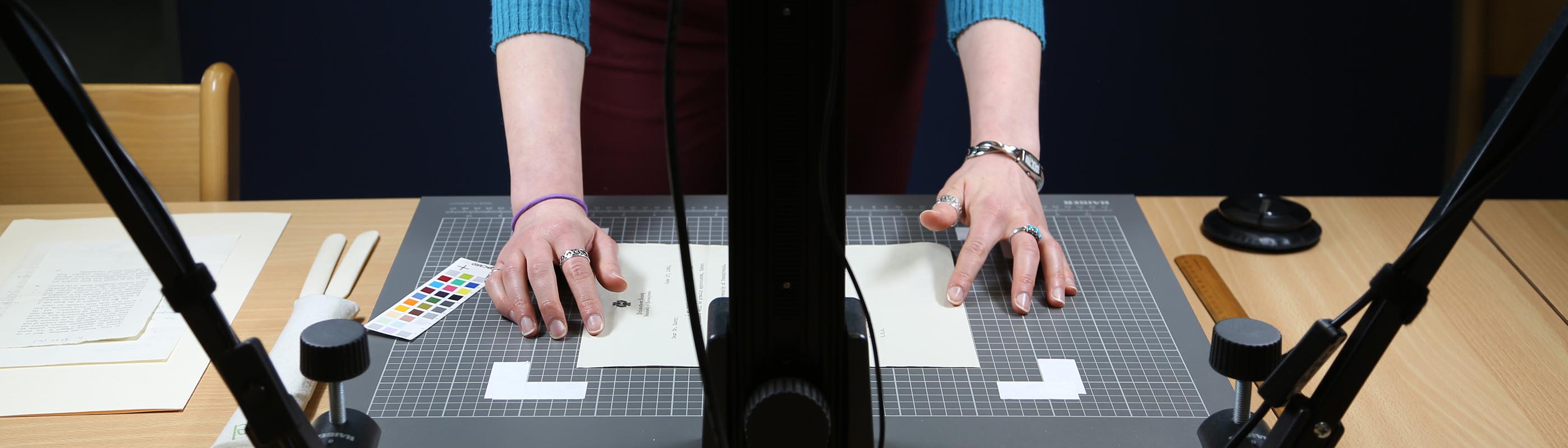

Digitisation of the panorama first began in 2019, when the scrolls were initially brought to the Digital Humanities Lab’s archive store. To undertake imaging of the panorama, it was placed on a large copy-stand, with a medium-format Phase One IQ3 100 mega-pixel camera and an 80mm Schneider-Kreuznach lens mounted vertically above. It was also important for the digitisation process to take place in a controlled environment, with balanced light coming from two downwards facing angles to avoid shadows emitting from equipment or the photographer.

Given their size and fragile nature, it made sense to digitise the panorama in segments as opposed to capturing the entire scene in one photograph. This has the advantage of capturing much richer detail while ensuring part of the panorama remains in scroll-form, thus avoiding any possible damage to flattening the entire object at once. With this method, however, comes a much greater processing time, including further attention to re-stitching the images together on Photoshop, though is generally considered more practical for large fold-out prints and manuscripts. Each part was held and manoeuvred using weighted beanbags, snake-weights, and bone-folders, ensuring they were handled and moved with care. A glass screen was also used to hold the panorama in place, partly to allow easing out of any creases but further to avoid the possibility of compromising photographs at later stages of the digitisation process, where misalignments caused by non-flat surfaces might occur.

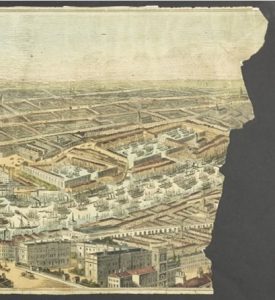

The second part (right-side) of the panorama further proved problematic since it has a tear spanning its entire width. The damage, as shown in Figure 7, includes a large tear down one edge, with the ripped portion now missing entirely. Given the scope of this project, as well as intrigue into which scenes of the panorama were missing, the decision was made to digitally revive this part of the panorama, by cropping and stitching a fine line copy of the Panorama of London, part of the British Museum’s collection and available to view on their website. This fine line (as opposed to coloured) copy of the panorama is quite possibly an earlier example of the twelve-page print, as originally published by William Little at Strand for the Illustrated London News.

Figures 9 and 10: Damaged edge of the panorama. Shown stitched to a fine-line copy held by the British Musuem.

Certainly, the differences in digitisation techniques came to the fore in this process, since the British Museum has likely provided an ‘access’ copy as opposed to a high-quality Tag Imaged File Format (TIFF), as was used in our own digitisation of the panorama. This latter file (‘lossless’ as opposed to ‘lossy’, such as JPEG files) captures the formal and material characteristics of the print, as well as information pertaining to the digitisation process, thus is better suited to archival preservation. The comparative difference between the two copies can be seen in Figure 7 or by zooming in on the story map online.

Following the stitching process, the complete panorama was exported from Photoshop using Zoomify, a file generator which splits an image down into small tiles, enabling delivery of high-resolution and zoomable imagery. As such, when scrolling towards the panorama, each view is that of a new image as opposed to a zoomed version of the complete panorama. This has the benefit of enabling the page to load quicker while retaining higher resolution.

Using Knight Lab’s (Northwestern University, USA) StoryMapJS tool[1], we were then able to overlay a series of slides on top of the panorama, creating a narrative effect which can be used to navigate through various scenes. StoryMap is usually applied to geographical maps as opposed to pictorial images, so creation of the story tool first required translating each pixel of the panorama into geographical coordinates to suit the open-source JavaScript released by Knight Lab. Each of these points represents distance in relation to other parts of the print and designated ‘points of interest’. Whether it be St Paul’s Cathedral or the New London Bridge, and so on, we were then able to be attribute the various scenes of interest to co-ordinates as a result. Each slide was then filled with a title, description, and associated image to generate a narrative arc to the Story Map.

In sum, the Story Map brings a greater sense of awareness to the various buildings, bridges, and intricate scenes which have deliberately been elevated by Smyth in his illustration. In this sense, it encourages viewers to think reflexively about their own experience of viewing the panorama, while reflecting upon how this might differ to a reader of the Illustrated London News in 1845. Smyth’s artistic license omits the harshest and most unpleasant parts of nineteenth century London, yet it stands as an excellent example of how meaning was generated for and by readers of the magazine. Smyth’s subjective view of London is thus given a second voice, though one which is ultimately framed within the remit of a partial and conservative interpretation of nineteenth century London. [1] See https://storymap.knightlab.com/ for more on this.

[1] See https://storymap.knightlab.com/ for more on this.

Hi. I went looking for an online version of this image after seeing a large reproduction at the Greenwich Maritime Museum. It was difficult to study up close and hard to get the full experience due to a royal barge being up against it.

Excellent storymap and great work overall, but one error to report unfortunately. The ninth story slide entitled “Nelson’s Column” is actually pinned to the Duke of York Monument just off Carlton House Terrace. Nelson’s Column is further East of this.

Apologies if this is one you keep getting!

Cheers

Thanks, Chris, and we’re glad you found the storymap to be an accessible way to study the panorama, we enjoyed putting it together! We’ve now corrected the error with the ‘Nelson’s Column’ story, which should point to the correct landmark – it might need you to clear your browser cache to pick up the change – thanks for pointing this out to us. We’re currently discussing revisiting the panorama, and possibly adding further London landmarks. This project came about in part because the copy in our Bill Douglas Museum seemed too good an opportunity to miss, and the research into the British Library copy opened up some useful collaborations. We’re hoping to identify suitably detailed panoramas and maps of other locations for future projects.