We recently spent a week at the Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives, working on a very exciting new project to digitise the Exeter Book.

The book

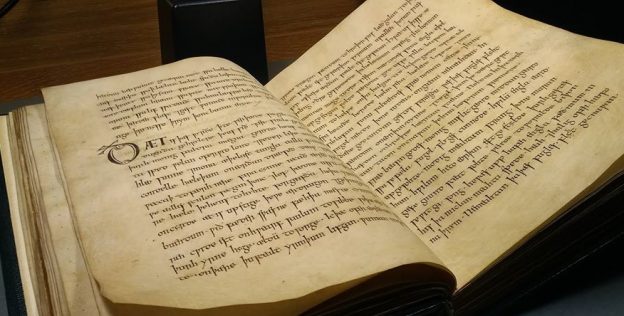

The Exeter Book is the oldest of only four examples of Anglo-Saxon poetry manuscripts still surviving today. Of these surviving manuscripts, it contains the largest collection of Old English poems and riddles still in existence. It was most likely complied in the years 960-990, and was donated to the Cathedral by Leofric, the first Bishop of Exeter, on his death in 1072.

It is written in dark brown ink on vellum pages, with no colour and little ornamentation. On a few leaves, drypoint drawings that were not part of the original design of the book have been scratched into the pages with a stylus. Some of the leaves are damaged, particularly at the beginning and the end of the volume, and several leaves are missing.

It has been used as part of the inspiration for many creative works, including poems by W. H. Auden and Ezra Pound, and for J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, but has also been put to less illustrious uses over the centuries, seeming to have been used as a chopping board at one point, and as a press for gold and silver leaf, which has left small traces on some of the pages.

The project

The work we carried out that week was to digitise the book so that we have a high-quality digital surrogate that can be made available to as wide an audience as possible.

Our work throughout the week was split into two stages: the first was to digitise a complete copy of the book; and the second was to try to capture images of the drypoint illustrations that appear within the margins of some of the pages.

Photography

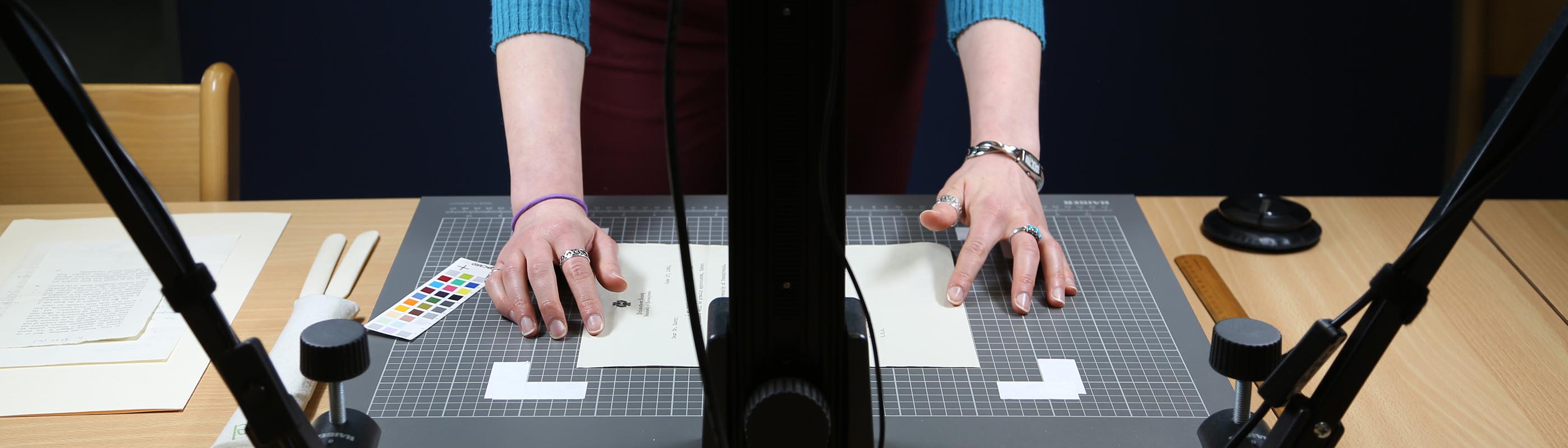

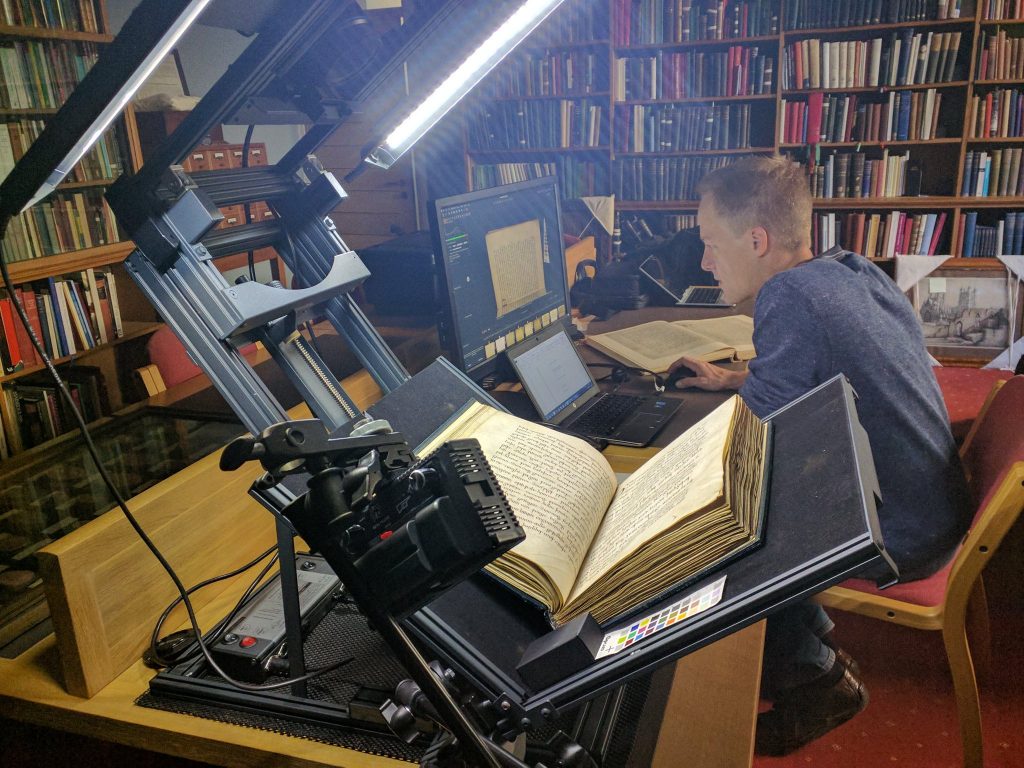

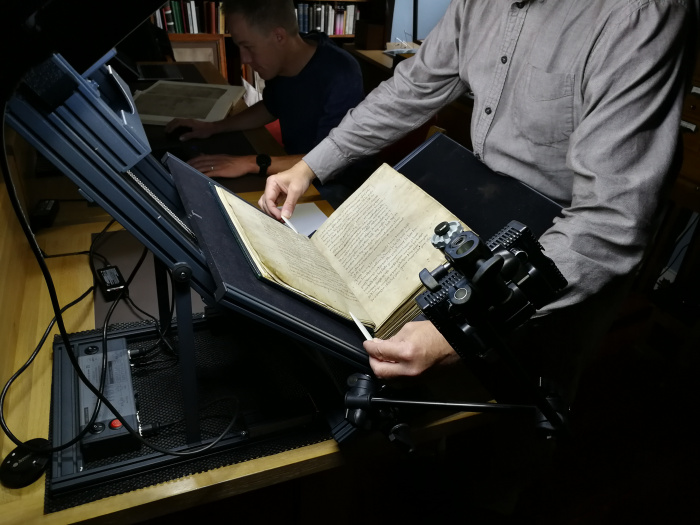

We used our portable copystand to support the book while we took the photographs. The camera is positioned in the stand so that it is looking down on one half of the open book, with one page is fully in shot at any one time. The page does not always sit flat, and sometimes has to be held in place with bone folders (archival instruments made of bone). Conversely, if the opposite page is bowed, it sometimes has to be held back so that it doesn’t get in the way of the page we want to photograph, as pictured below. For the page we are photographing, we try to manage without the bone folders as much as possible, and to keep only the minimum possible visible in shot if we do have to use them. This will mean that we end up with as much of the original visible in our final version as possible. We are lucky that the binding of the Exeter Book is loose enough to permit relatively consistent flat page images for most of the volume. Even when the page bows a little, our camera setup has a large enough depth of field that the image will still be crisp and sharp.

We had two people working on the photography at once: one turning and positioning the pages, and the other setting the focus, taking the images, and then checking the focus and the quality after each image was taken.

All of the images are taken in the same controlled lighting conditions, so that we had consistent lighting throughout the week for all of the pages. Staff at the Cathedral even had to block up the windows for us in the room we were in for the week.

To take the images, we first photographed all of the verso (left-hand) pages, going through one complete pass of the book until the end, and then photographed all of the recto (right-hand) pages all of the way through the book. Although this means that we will later have to stitch together the two sides of the page from the two separate photography sessions, organising our photography this way has the advantage of minimising our handling of the book. Otherwise, if we had to turn around and reposition the book after every page photographed, we would be putting a lot more strain on the binding and handling the pages a lot more than necessary.

We position a colour card next to the book for each photograph, which allows us to judge our images against a standardised set of colours in post-processing, and adjust the colour profile accordingly if necessary.

Drypoint marks

A view of a drypoint illustration on folio 78, captured with a raking light source (via Laurence Blyth, Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives)

To capture images of the drypoint illustrations, we used a raking light and experimented with different angles in order to best illuminate the images, taking several images of the same drypoint to find the angle that illuminated the detail most clearly. The drypoint illustrations are scratched into the surface of the manuscript rather than being drawn with pen and ink (as though you were to take the wrong end of a pen and carve into the paper with it), and often the markings are so fine and so shallow that they are very difficult to see with the naked eye. In fact, even when we knew there was a drypoint on a certain page, we often still had a lot of difficulty in spotting it until we used the raking light to enhance the shadows and make it more clearly visible. Amongst other things, the Exeter Book hides drypoint illustrations of decorative flowers, a horse and rider, and of an angel, pictured above.

We would like to thank all of the friendly staff at the Cathedral Archives for their help and assistance in the week, and we look forward to working closely with them as the project progresses.

Further reading about the Exeter Book

‘#HobbitDay and the Exeter Book’. Exeter Cathedral.

‘Digitising the Exeter Book‘. Anglo-Normantics.

‘10 Things You Should Know About the Exeter Book‘. BookRiot.com