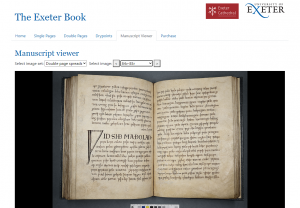

The new online platform for the Exeter book is now live, making one of the oldest surviving volumes of English literature in the world fully accessible to the public for the first time.

The new online platform for the Exeter book is now live, making one of the oldest surviving volumes of English literature in the world fully accessible to the public for the first time.

The new platform has already been generating lots of interest, especially through Exeter’s role as a UNESCO city of literature, and since this kind of digitisation might be new to many of those interested, we thought we’d share a behind the scenes tour of what goes into creating the high definition images that make it possible to explore the tiny details of a 1,000-year-old manuscript on your phone.

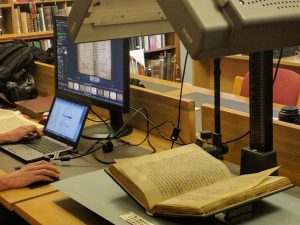

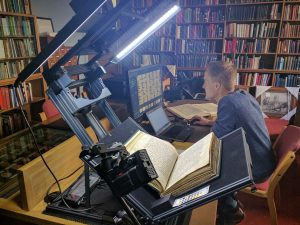

The digitisation took place during a week-long trip to Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives, the home of the Exeter book. As the book is too precious to transport, the Digital Humanities team packed up two copy stands and a lot of camera and lighting equipment, and headed across Exeter to the Cathedral, where the Library and Archives team gave us a very warm welcome while we turned their reading room into a temporary digitisation lab.

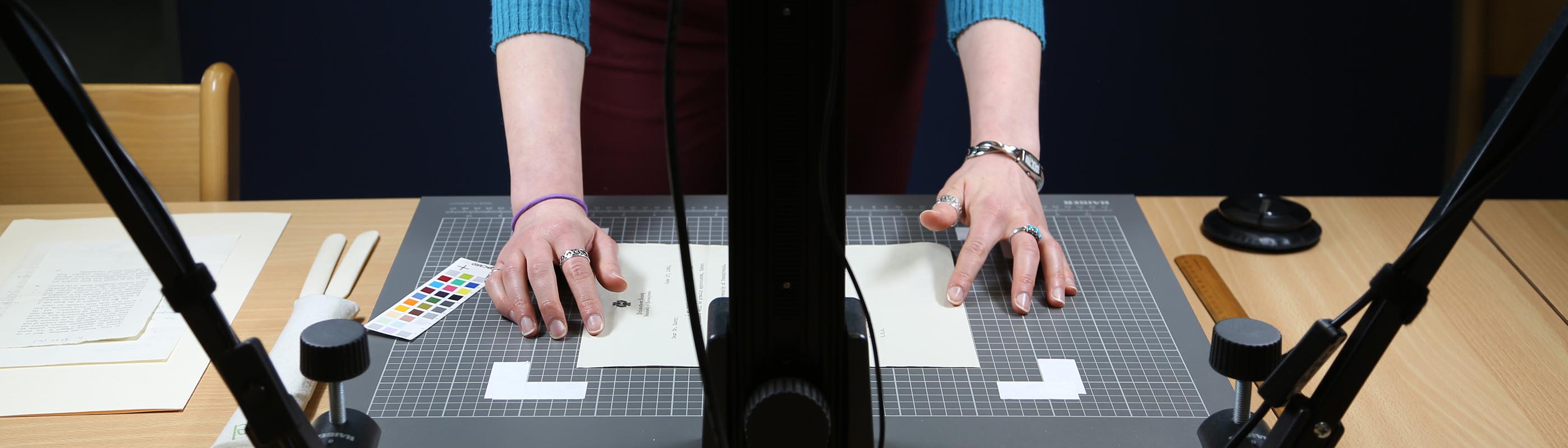

The main aim was to take very high resolution photographs of each page, enabling them to be studied in close detail. For this project, the team used a 100 megapixel PhaseOne camera with a 120mm macro lens to capture as much detail as possible. The camera was connected to a computer, allowing the photographs to be captured though the CaptureOne camera software, so that features like colour balance could be measured and adjusted to represent the original as faithfully as possible.

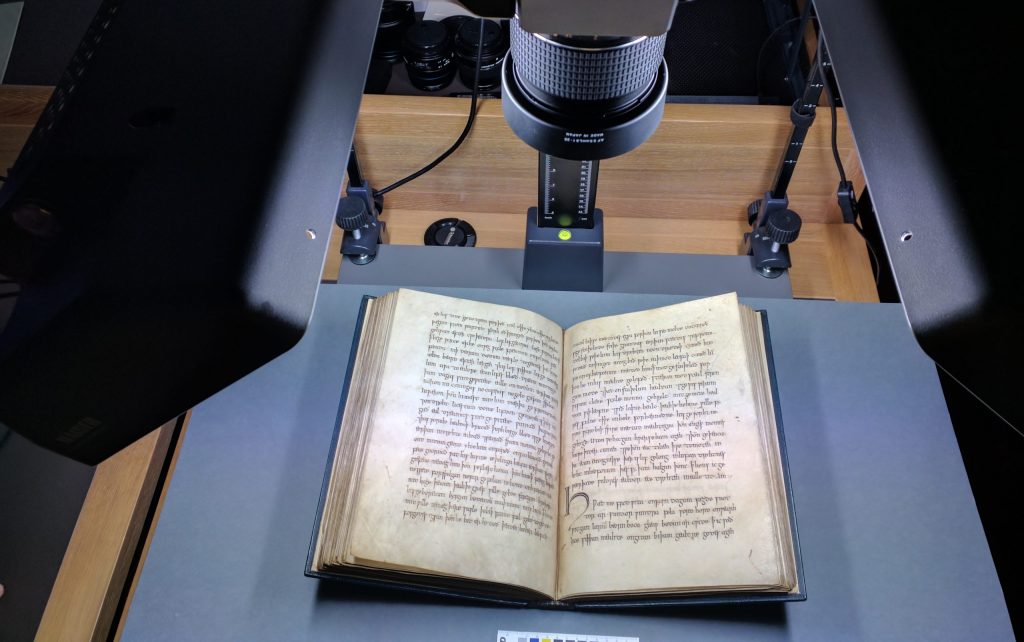

The conservation cradle in action

The book was supported on the lab’s conservation cradle – a specialist copy stand designed for easily photographing individual pages of bound volumes like the Exeter Book, without risking damage to historical bindings. Conveniently for this project, the cradle also packs down into a suitcase!

Single page images are excellent for providing the best views of each page, but there’s nothing like getting a full view of the entire double page spread, to get a sense of what the book is really like and how the poems are laid out on the page. So after spending two days photographing all the pages individually, the team moved the camera to a flat copy stand, with the book supported on an archival cushion, to capture the double page spreads.

Photographing double pages like this is much trickier than single pages. As the surface is no longer flat, it’s more difficult to get the whole book in focus. But by taking extra care with the depth of field, and paying special attention to the difficult areas between the pages, the double pages are now available alongside the single pages, so the book can be appreciated online just as the original readers would have experienced it.

One of the most fascinating and unique features of the manuscript is the handful of drypoint drawings scattered in the margins around the text, and we were really keen to photograph these enigmatic little images individually. As they were drawn without ink, they are virtually invisible unless lit from the right direction, so they don’t show up well in standard photos, and are very difficult to find in the manuscript unless you know where to look. The team used a catalogue of the drypoints made by Patrick Connor (1993: Anglo-Saxon Exeter. The Boydell Press, p. 122) to find them. However, since we haven’t examined all the pages in detail, it’s possible that there are still some hiding among the pages, that haven’t been noticed and digitised yet.

Lighting was key when photographing the drypoints. The best approach for revealing this kind of texture is raking light, held at a shallow angle to the page, and since they look different with the light from different directions, the team photographed them several times, using a handheld lightpack as an easily moveable light source. The resulting images give a much clearer view of the drawings than the standard images – try comparing the angel in the top right corner of folio 78r with raking light and without. Viewing them using multiple photographs is still not perfect though, and the team would really like to try photographing the drypoints again using reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), to create an all-round interactive view, which would allow the tiny details to be examined more closely.

RTI would also be very useful in helping to identify a ‘mystery’ drypoint. Previous studies suggested that there was a drawing in the bottom right corner of folio 96r, but the team haven’t been able to find any visible markings in the photographs. Hopefully RTI can shed some light on whether there really is a drawing on this page – otherwise there may be one fewer drypoint than previously thought!

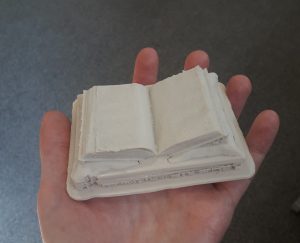

As a final touch at the end of a busy week of digitisation, the team brought out one more method to make the Exeter book digital – taking a quick set of photos for photogrammetry. There was only time to take 25 photographs to build into a 3D model, so the result is a little rougher around the edges than the models we usually produce, but it gives you an all-round view of the book, much like the one you’d get if you were in the cathedral reading room itself. We even had a go bringing the digitisation process full circle by using our 3D printer to make a physical version, although the 10th century text unfortunately doesn’t quite make it through to the final print!

Combining these different digitisation methods gives readers a rare experience of the Exeter book – without the limitations of protective glass cases, in more detail than ever before, and with complete freedom to browse and explore, and there’s plenty of potential for experimenting with other methods in the future, to continue to make this ancient treasure new, relevant and engaging.

View the Exeter book online.

Many thanks to the Library and Archives team, and particularly Ann Barwood and Ellie Jones, for all their help and support during the digitisation process.